What happens to our bodies when they get hot?

Humans might live in all kinds of climates, from the Arctic chill to the searing Sahara desert, but we have evolved to survive with an average core body temperature of 37 degrees (give or take half a degree). Too cold and we get hypothermia. Too hot and it’s hyperthermia – dangerous overheating. Professor Ollie Jay, director of The Heat and Health Research Incubator at the University of Sydney, has studied both phenomenons, having lived in wintry Wales and Canada, and now running the Thermal Ergonomics Laboratory in Australia. When the outside temperature stays within our so-called “thermoneutral zone” of about 20 to 25 degrees, our bodies don’t need to do anything much to maintain our core body temperature. But when the weather warms up, Jay says, two main defence adaptations kick in. And both start in the skin.

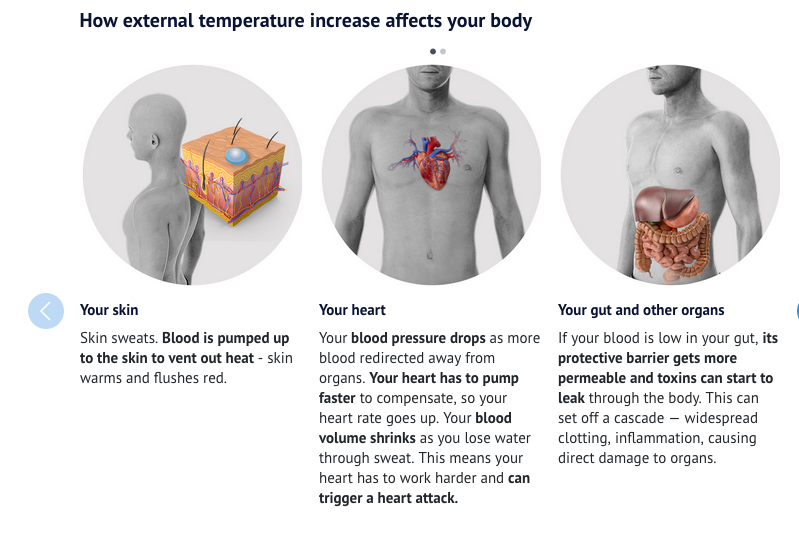

The first we know well: sweat. The second is just below the surface – blood vessels dilate to pump blood up to the skin and allow more heat to vent out of the body. Sweat alone does not cool you down, says Jay, who has worked with Cricket Australia and the Australian Open on their heat policies to protect players. It’s sweat evaporating from your skin that does the trick. But if it’s humid, with lots of moisture in the air, or not much airflow, that becomes harder. Eventually, you can hit a point where your sweat can’t evaporate properly and your core body temperature will keep ticking up and up.

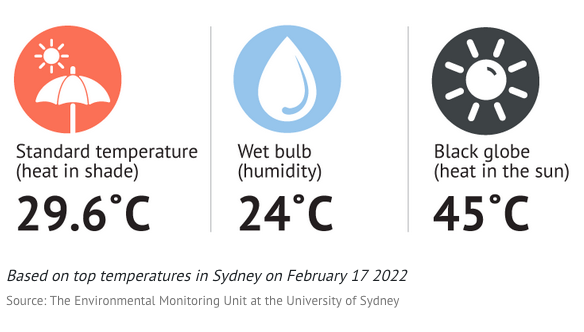

What are ‘wet bulb’ and ‘black globe’ temperatures?

As climate change drives both hotter and wetter weather around the globe, experts are looking beyond the standard temperatures issued by the Bureau of Meteorology to “wet bulb” temperature. That measures humidity as well as heat, using a thermometer covered in a wet cloth to gauge evaporation. The number will be lower than the weather forecast, but every degree has a bigger impact.

In fact, the highest wet bulb temperature humans can survive is about 35 degrees – beyond that we can no longer cool ourselves via sweat evaporation and can die after a few hours, even in the shade drinking water. “Thirty-five degrees [wet bulb] is about survivability, everyone will die,” explains Jay. “But before that, we have severe impacts on liveability, and the most vulnerable can die.”

A 2020 study found that global warming is pushing up wet bulb temperatures faster than expected. Parts of the Middle East and south Asia are approaching the deadly 35-degree threshold (even briefly crossing it) and will probably regularly cross it by 2075. Up north in Australia, Quilty says, people in humid Katherine often fare worse at 35 degrees on the regular forecast than those in the drier Alice Springs do at 40. “And when you get high humidity with heat, it’s incredibly dangerous. In 2019 in Katherine, we had 54 days above 40 degrees. The average is six.” Jay says wet bulb temperature is an “elegant” way to underscore the importance of humidity but there are other factors to consider too, such as wind and sun.

Wind will affect how well your sweat can evaporate. “We all know that sweet relief of a breeze,” says Jay. But without it, you’re in even more trouble. As one scientist pointed out, wet bulb temperature assumes maximum airflow, the equivalent of “a naked, healthy adult standing in the shade with gale-force winds blowing on them while they were drinking gallons of water”.

Meanwhile, so-called “black globe” temperature measures solar radiation. “In summer, it’s about 15 degrees higher in the sun than in the shade,” Jay says. “But the temperature you get from the bureau is the shade so using that alone as an indication of your risk is fraught with problems.”

In western Sydney, Loo says, temperatures are often “6 to 10 degrees hotter than the rest of Sydney”. She describes the rows of black roofs, of baking fake turf and concrete, and few trees to keep out the heat. Penrith was the hottest place on Earth during the height of the Black Summer bushfires (although records tumbled again this January when the outback town of Onslow, Western Australia, hit 50.7 degrees). Jay’s team is working on a more robust approach to heat risk that looks at someone’s age, sun exposure, activity, even their clothing As we age, we sweat less. And, as we move around, our muscles generate heat inside our body. “So this heat needs to be vented out through the skin,” Jay says. “If you encased yourself in a suit – imagine the thickest, most insulating suit – you’d cook yourself in six hours just sitting down. So for people working outdoors in the sun, .maybe wearing protective clothing, moving a lot, suddenly these other factors become very important.”

How does heat kill you?

Our 37-degree core temperature is the optimum level for our body’s internal chemistry to function, Jay says. So, while a difference of a degree or two might not feel like a lot outside, inside it can quickly send things off kilter. (“We are always about 4 or 5 degrees away from catastrophe.”)